Designed by rawpixel.com / Freepik

Designed by rawpixel.com / Freepik

As for any project, before digging into the technicals you need to define your goal clearly. This means defining the features, the interactions, as well as the metrics to declare the project a success. The more you formalize your specifications, the more data you will have to work with during the next steps.

This article is not specific to distributed systems and can be applied to any kind of project.

Define Features Through Intended User Experience

Any application solves an initial problem, the term being used here in a broad sense. It can vary from very concrete (e.g. generating subtitles from a video) to more abstract ideas (e.g. improving privacy on the internet).

The first operation to perform here will be to uniformize all problems to concrete and meaningful user stories. As the name hints, those stories should always start from the point of view of your users since you are designing the application for them. A user story will take the form of “As a …, I want to … so that …”.As a side note, starting from the customer's point of view is the first principle of Amazon and is often relayed as the key to their success.

Once you have a list of applicable user stories, you need to sort the stories into two categories: the ones critical to your application (a.k.a. must have) and those that can wait before being integrated (a.k.a. nice to have). The collection of your must-have stories will constitute the minimal viable product (MVP).

Note For Interviews: The MVP should be defined along with the interviewer, which will select a scope of features that can be analyzed during the session.

Extract Components From Created Domains

From your user stories, you should be able to group features semantically tied together. Such a group can be considered as a domain in the concepts of Domain-Driven Design. The number of domains depends solely on the complexity of your project and there is no silver bullet when it comes to separating a project into domains. Too many domains can slow down your development and make it cumbersome, while too few puts you at risk of having tightly coupled code, which decreases maintainability in the long run. Usually, starting with a few domains is the right call, as it will help you quickly draft your system while giving you time to find the right abstraction.

This extraction of domains will define the segregated components in your software that should communicate through a public interface. Nowadays, this is often represented as independent micro-services, but it can also simply be done through packages inside the same component of a monolith.

Note: The choice is not critical at this point, but the advantages and drawbacks of each architecture are discussed in Monolithic vs. Microservices Architecture by Anton Kharenko.

Explicit Contracts Between Components

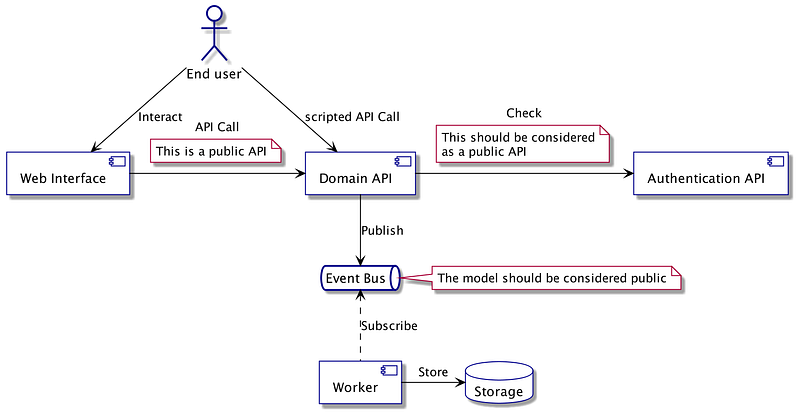

It is important to be clear from the beginning about your system's public inputs and outputs. On top of the interactions with the end-user, every interaction between domains should be considered a public interaction. Hence, a contract should exist defining common methods and data models for communication. Those interactions can take multiple forms depending on the implementation, so the interaction contracts can be formatted with abstract model definitions at first.

The public models will usually match the internal ones, and it could be enticing to use the same models with both private and public code. However, the internal model will most likely change over time, and potentially break compatibility with the existing contract. To ensure that external interactions will not be affected by such changes, you should segregate internal and external representations of your domain. One way of ensuring this is using a hexagonal architecture. Netflix wrote a very informative post about their migration to such architecture.

As a matter of representation, let’s consider a web service accessible through both a user interface on a browser and an API. The reason why the API should not change is pretty clear, even if you can change the web interface according to your new API, if you do not hold a clear and immutable contract, customers will have trouble keeping their scripted calls alive. In the same fashion, interactions between your components are the same. Indeed, when your application will grow, you may have different teams working on each component, one team becoming the customer of the other.

Example of Interactions in a Distributed System

Example of Interactions in a Distributed System

Build the Present, Keep an Eye on the Future

Even if they are not implemented at the moment, the nice-to-have user stories are important in a way. They define the long-term goal you want to achieve and could be significant while defining the technological stack or integrating some must-have user stories.

As a trivial example, let’s say that we want to integrate a feature transforming .svg files to .png. Maybe this is the only transformation that will take place ever in the project, in which case it’s fine to do a specific implementation. On the other hand, you may have planned to transform multiple formats to .png. In this case, you will most likely consider a modular approach from the start, to reduce the cost of further integration.

Sometimes it will be too costly to prepare for the future, and that’s okay, as long as you are aware of the technical debt you create and integrate the cost of removing this debt in future work.

Define Metrics to Assert Success

Defining the right metrics is critical to know the health of your project, both on the technical and applicative side. It will give you directions to further enhance your product.

On the technical side, you can consider some out-of-the-box metrics. For instance, Google defines the Golden Signals as Latency, Traffic, Errors, and Saturation. A view on at least those four metrics should give a good status of the application’s technical health at any time, and combining them with alerts will help you keep your business available and responsive.

On the applicative side, the metrics will be more specific to the features. The main objective will be to ensure that the users are using the features as expected, in other words, that you correctly foresaw their needs and that your design is intuitive. Among the tips that are usually given, the ones that seem the most important are:

Choose a few metrics, if not only one. Too many of them may be correlated and less actionable if you have mixed signals.

Avoid metrics that are here to make you feel good but give no real insight into your product's health.

This is definitely a hard subject to master, so I can only recommend you to dive deeper into the subject, starting with How To Measure The Success Of Your Feature? and Defining Product Success: Metrics and Goals.

Conclusion

We saw the non-technical decision process to make while designing a system. This process will end up creating features that should mostly:

Initiate from a customer need.

Follow the Keep It Simple, Stupid principle as much as possible.

Have a feedback loop to detect issues and improve usage.

You will end up with a set of contracts that you will have to honour during the next step: the technical design.